Sargassum seaweed is washing ashore at low levels on Southeast Florida’s Atlantic beaches, according to the latest observations by the Sargassum Watch database maintained by Florida International University.

And it’s likely to stay that way until May, according to the April forecast by the University of South Florida’s Optical Oceanography Laboratory.

In a normal year, the sargassum seaweed “season” on Florida beaches begins in April or May and continues into summer. Heaviest hit in most years are the Florida Keys.

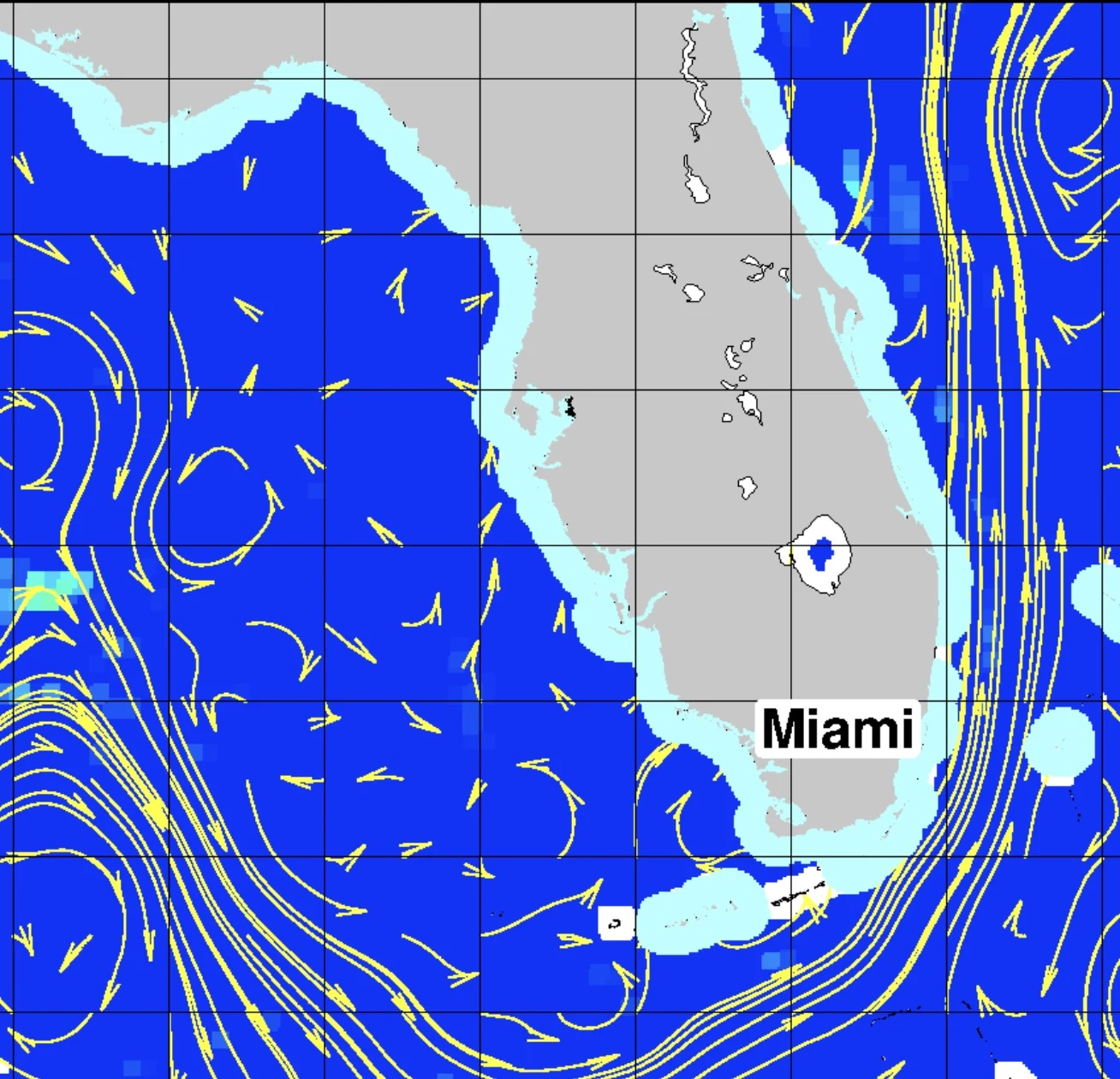

Sargassum blooms arise in the Central Atlantic annually in December and drift westward into the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico during spring and summer.

The floating seaweed provides beneficial shelter from the sun and food for fish offshore, but becomes a nuisance and potential health hazards after it washes up on beaches.

Related stories:

- Sound at sea, sargassum buries beaches and threatens tourism, WUSF, 4/14/2024

- FAU lands grant to clean up stink seaweed, FAU, 4/10/2024

- Sargassum buries beaches and threatens tourism, WGCU, PBS Southwest Florida, 4/11/2024

- Sargassum 2024, KeysNews.com, 4/11/2024

Sargassum seaweed is not a new phenomena, but the 5,000-mile-wide mass recorded offshore during the spring and summer of 2023 was the largest ever recorded.

Florida’s seaweed season typically runs from April until October, peaking in June and July. The seaweed comes in batches, depending on currents and wind direction.

The seaweed itself is not harmful to humans, but decaying sargassum on beaches releases hydrogen sulfide that can impact people with breathing issues.

That said, even decaying sargassum is not considered harmful because the gases disperse quickly on breezy beaches.

New research suggests the pathogen Vibrio sticks to microplastics that merge into sargassum clusters at sea, and while the bacteria has not been detected in sargassum washing ashore, beachgoers are advised to keep their distance from seaweed clusters.

Vibrio vulnificus, one of more than 100 species of Vibrio, sometimes referred to as flesh-eating bacteria, can cause life-threatening food-borne illnesses from seafood consumption as well as disease from open-wound infections, according to the national Centers for Disease Control.

You might think the seaweed would be removed from the water before it hits our beaches, but that’s against the law because of it’s value as a shelter and food source for marine life.

Indeed, these seaweed “lines” are popular targets for anglers who troll for mahi-mahi and other gamefish.

Once the sargassum blob hits the beach, the seaweed can be removed.

Popular tourist beaches rake the seaweed each morning and remove it from beaches, but with the state’s 1,350 miles of shoreline, that’s not always possible.

Resource for you: Sargassum Information Hub

Beach Cams around Florida

Sargassum seaweed arrives in waves, depending on wind direction and currents.

These links will take you to live beach cameras at popular Florida beaches so you can see for yourself in real time.

Atlantic Beaches (North to South)

- Jacksonville Beach (surfguru.com)

- St. Augustine Beach (surfstationcam)

- Flagler Beach Pier

- Ormond by the Sea

- Daytona Beach

- New Smyrna Beach

- Cocoa Beach (Jetty Park)

- Cocoa Beach

- Melbourne Beach (surfguru.com)

- Sebastian Inlet (surfguru.com)

- Deerfield Beach

- Lauderdale-By-The-Sea (earthcam.net)

- Fort Lauderdale Beach

- Dania Beach

- Hollywood Beach

- Miami Beach

- Key Biscayne

- Islamorada (Beach at Amara Cay)

- Marathon (Beach at Tranquility Bay)

- Key West (Fort Zachary Taylor Beach)

Gulf Beaches (Panhandle to South)

- Pensacola Beach (visit pensacola)

- Destin (surfguru.com)

- South Walton / 30a Beach Webcams

- Clearwater Beach

- Indian Shores (surfguru.com)

- Treasure Island (surfguru.com)

- Siesta Key

- Venice Beach (Sharkey’s on the Pier)

- Fort Myers Beach

- Naples Beach

Sargassum FAQs

What is Sargassum?

Sargassum is a type of floating brown algae, commonly called “seaweed.” These algae float at the sea surface, never attach to the sea floor, and they can aggregate to form large mats in the open ocean.

Where does it come from?

Historically, the majority of Sargassum aggregated in the Sargasso Sea in the western North Atlantic, with some small amounts found within the Gulf of Mexico and Caribbean Sea.

In 2011, the geographic range expanded, and massive amounts of Sargassum moved west into the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and south tropical Atlantic, washing ashore in Florida, Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, and most islands and coastal areas in the Caribbean Sea.

What are the benefits of Sargassum?

Sargassum, in normal amounts, provides habitat, food, protection, and breeding grounds for hundreds of diverse marine species, including commercially important species, such as tuna and swordfish, which feed on the smaller marine life present in Sargassum mats.

If Sargassum reaches the coast in small/normal quantities, it may help to avoid beach erosion.

What are some of the drawbacks of Sargassum?

As Sargassum accumulates close to the coastlines, it can smother valuable corals, seagrass beds, and beaches. As it washes ashore the seaweed begins to decay, attracting flies and other insects.

During its breakdown, Sargassum produces hydrogen sulfide gas, which smells of rotten eggs, repelling beachgoers.

Sargassum can also impact navigation, block water intake in desalination plants, and impact benthic ecosystems after/if they sink to the bottom of the ocean.

What threats, if any, does Sargassum pose to human health?

Studies of the impact of Sargassum on human health started very recently and this is a topic that needs more time to be fully understood. However, when decomposed, Sargassum releases hydrogen sulfide (a gas) that may cause respiratory health problems. Sargassum is also known to often contain heavy metals that can be toxic to humans and animals.

What about reports of ‘flesh-eating bacteria’ in sargassum?

In the open ocean, researchers at Florida Atlantic University discovered the pathogen Vibrio sticking to microplastics that merge into sargassum clusters at sea.

Vibrio vulnificus, one of more than 100 species of Vibrio, sometimes referred to as flesh-eating bacteria, can cause life-threatening foodborne illnesses from seafood consumption as well as disease, even death, from open-wound infections, according to the national Centers for Disease Control.

Kevin Johnson of Florida Tech’s marine sciences department, says the FAU research “has not demonstrated the sargassum coming onshore is especially dangerous with regard to bacterial infection for people.

Many of the bacteria that are associated with those plastics and sargassum are already present in our environment.”

What you should know about flesh-eating bacteria on beaches, CNN, 6/9/2023

“I don’t think at this point, anyone has really considered these microbes and their capability to cause infections,” says FAU biologist Tracy Mincer. “In particular, caution should be exercised regarding the harvest and processing of Sargassum biomass until the risks are explored more thoroughly.”

Sargassum removed from beaches is frequently used in fertilizers.

Does Sargassum cause skin rashes and blisters?

Sargassum does not sting or cause rashes. However, tiny organisms that live in Sargassum

(like larvae of jellyfish, sometimes called sea lice) may irritate skin if they come in contact with it.

Why did the geographic range for Sargassum expand in 2011?

Researchers are still assessing various hypotheses about the cause of this first documented extreme event.

One hypothesis proposes that during the winter of 2009–2010, the winds that typically blow to the east, from the Americas to Europe, strengthened and shifted to the south more dramatically and persistently than any other time in the 1900–2020 record.

This shift in winds triggered a long-distance eastward dispersal of Sargassum, from the Sargasso Sea, toward the Iberian Peninsula in Europe and West Africa.

After exiting the Sargasso Sea, the Sargassum drifted southward in the Canary Current and entered the tropics.

Once in this new and favorable tropical Atlantic habitat, with ample sunlight, warm waters, and nutrient availability, the Sargassum flourished and has continued to grow.

In addition to changing wind patterns, other hypotheses include a combination of factors, such as the variation in the outflow of major rivers (e.g. Amazon and Orinoco), nutrient (nitrogen and phosphorus) concentration in the oceans, increase in the amount of phosphorus due to saharan dust, water temperature, and river runoffs.

Having established a new population, the Sargassum now aggregates almost every year, starting in January/February in a massive windrow or “belt” north of the Equator, along the region where the trade winds converge.

During the late winter and early spring months, the Sargassum moves northward with the seasonal winds and currents. By June, this belt may stretch across the entire central tropical Atlantic. Large portions of this algae are then transported into the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico via the North Equatorial and Caribbean current systems.

Is the amount of Sargassum in the Atlantic/Caribbean increasing?

Since 2011, large accumulations of Sargassum have occurred every year in the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, and tropical Atlantic, but the amount can vary from year to year.

The presence of Sargassum occurs over large areas from the tropical Atlantic in the east, to the Gulf of Mexico in the west, approximately 5,000 kilometers from the eastern tropical Atlantic to the west off the Mexican coast in the Caribbean Sea.

Sargassum does not extend as a blanket (or blob) covering the full surface of the ocean in these regions. Instead, Sargassum floats in patches that range in size from a few centimeters to hundreds of meters.

Some of these patches reach the coastal areas, including beaches, ports, and even intake systems for drinking water. The area that these patches cover has been significantly larger in recent years than prior to 2011.

Sources: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Coast Watch; Florida Department of Health Fact Sheet

Bob Rountree is a beach bum, angler and camper who has explored Florida for decades. No adventure is complete without a scenic paddle trail or unpaved road to nowhere. Bob co-founded FloridaRambler.com with fellow journalist Bonnie Gross 14 years ago.

Natalia Picardi

Wednesday 2nd of August 2023

Hi! I am planning to to do Lauderdale by the beach this weekend? How is the. Sargassum? Thank you so much’

Bob Rountree

Thursday 3rd of August 2023

Not enough to worry about. You may find occasional seaweed patches on the beach, but that's normal for this time of year.

Ranu

Wednesday 7th of June 2023

Hi. Planning a family trip to Naples Beach July 13-19. Was hearing we may be affected by sargassum weed? Will hate to be there and not be able to swim. Coming from Canada. Also concern about omeba. Should I reconsider visiting at this time?

Bob Rountree

Wednesday 7th of June 2023

The seaweed glut is easing along the Southwest Florida coast, according to the University of South Florida, and when I looked at the Naples Beach web camera this morning, there doesn't appear to be any seaweed at all on or near the beach. Here's a link to a live web cam: https://youtu.be/3VJGu5uD1bM. As for the amoeba, the only amoeba reported by scientists has been attached to microplastics caught up in seaweed far out in the Atlantic Ocean, according to the results of a study by Florida Atlantic University. Even with that study, there is no evidence any human interaction with seaweed has caused any medical issues. Obviously, the decision is yours to make. But personally, I don't think there's a lot of reason for concern.

Ana

Wednesday 7th of June 2023

Hi Bob, planning on going to crandon park in key biscayne this weekend. My elderly grandmother is freaking out because she heard about the flesh eating bacteria on the news. Are you familiar with this area? Do you think it'll be safe to swim? Appreciate you taking your time. Thanks

Ana

Wednesday 7th of June 2023

Thank you Bob, you've been most helpful. I too think it'll be fine

Bob Rountree

Wednesday 7th of June 2023

The seaweed seems to be easing up on South Florida beaches for now, so I wouldn't be concerned. As for the amoeba, there is no evidence that anybody has been affected by "flesh-eating bacteria." Researchers at Florida Atlantic University have only detected it on microplastics far out at sea, but there is no evidence of them washing ashore with seaweed. Obviously, the choice is yours to make. Personally, I don't think there's much of a threat. Here's a link to a live web cam on Key Biscayne so you can see for yourself. https://keybiscayne.fl.gov/uniquely_kb/kb_beach_cam.php

Brittany

Tuesday 6th of June 2023

We suppose to be going to Key West for a week starting June 17. My mother is concerned too. I'm not sure if we should cancel or not ? Any suggestions would be greatly appreciated.

Bob Rountree

Tuesday 6th of June 2023

I wouldn't let a little seaweed get in the way of your trip to Key West. There are far more distractions in Key West than a beach. The five public beaches are scattered around the island, and I doubt they would all have a sargassum problem at the same time. If you are still concerned, call your hotel or the host of your vacation rental. Whatever you do, have fun!

Sandy

Thursday 1st of June 2023

I am planning a weeks vacation in Destin Junee 11th . I just read an article that the brown seaweed can also carry flesh eating omeba. I am now freaking out. Should we consider not going.

Bob Rountree

Thursday 1st of June 2023

Kevin Johnson of Florida Tech’s marine sciences department, says the FAU research in the article you read "has not demonstrated the sargassum coming onshore is especially dangerous with regard to bacterial infection for people. Many of the bacteria that are associated with those plastics and sargassum are already present in our environment.”