Ask any aficionado of Florida Black history, and they’ll tell you that an easy way to learn how Black men and women have contributed to the story of the Sunshine State is to just hop in your car and follow the signs.

Of the more than 800 Florida historical markers that dot the state, a notable number recognize events and accomplishments involving Black Floridians who shaped our state and in some cases the nation itself.

Beaches, homesteads, schools — here’s a sample of some of the more interesting landmarks just a road trip away.

Beaches of Distinction

American Beach on Amelia Island

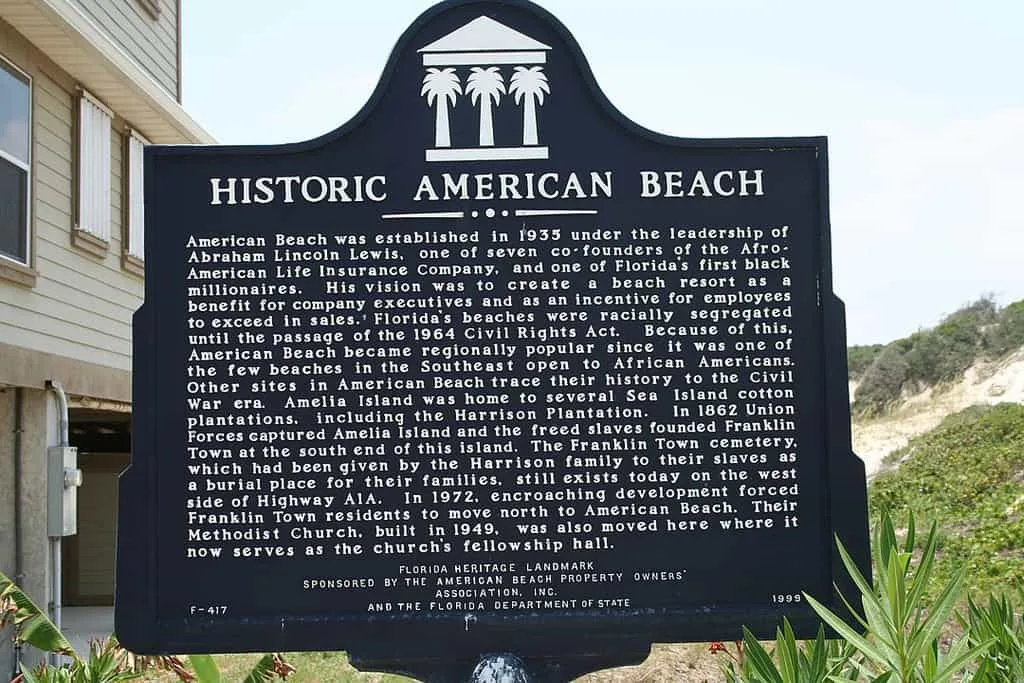

On the state’s northern edge on Amelia Island, American Beach was once a 200-acre beachfront resort, a nationally renowned vacation spot for African Americans during the days of legally enforced racial segregation.

Once a common practice in America, beaches, like many other parts of society, were racially segregated. Local governments across the United States enacted policies and practices that kept African Americans from setting foot on public beaches. Those same local officials also ignored pleas from Black community leaders for segregated Black beaches, and when they did find recreational areas for Black beachgoers, they often selected remote and hazardous locations.

The idea of a Black resort along the Nassau County coast was the dream of Abraham Lincoln Lewis, who owned a successful insurance company and was Florida’s first Black millionaire. He initially wanted a beachfront retreat for his clients and employees, but the reality grew far beyond that to include permanent residents.

In its heyday in the 1940s and 1950s, the beach attracted Black vacationers from across the South and luminaries like Hank Aaron, Cab Calloway, Ray Charles, Ossie Davis, Duke Ellington and Joe Louis.

Ultimately, integration prompted the demise of American Beach as Black vacationers were welcomed elsewhere. Over the years, the size of American Beach diminished under encroaching development, primarily new resort communities eager to be on the ocean.

What remains of the onetime Black beachfront paradise that offered “recreation, relaxation without humiliation” now contains the homes of a few remaining residents, the American Beach Museum, which boasts artifacts, photos and video presentations and three historic markers that describe the beach’s significance, the first home on the beach and the tallest dune system in Florida named after MaVynne Betsche, better known as “The Beach Lady,” a 25-year advocate for preserving the remains of American Beach.

Read more: Abraham Lincoln Lewis Museum on American Beach

Higgs Beach on Key West

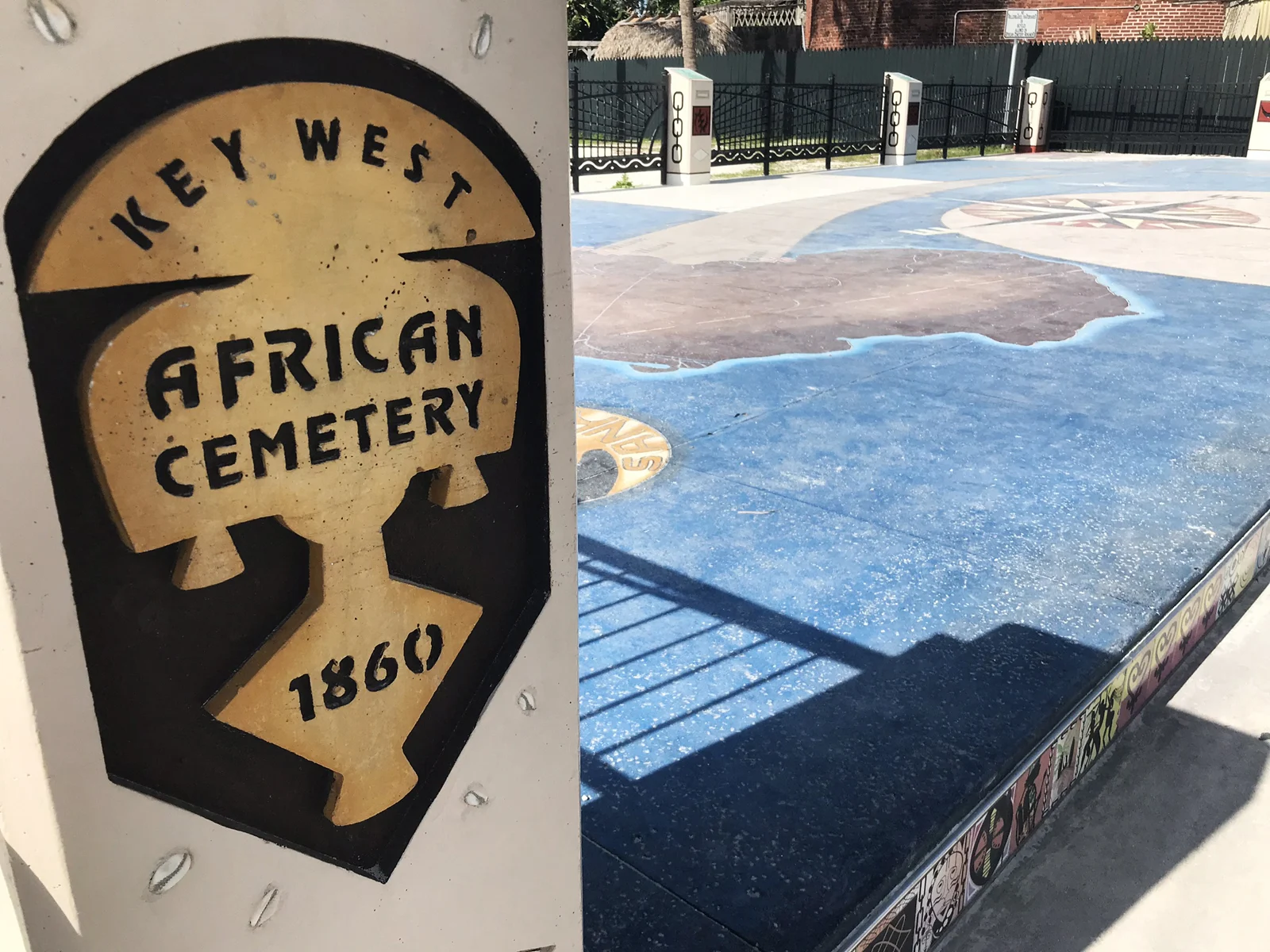

Near the southernmost point in Key West sits the Higgs Beach marker on a public beach that’s a combination beach strand, cemetery and stirring memorial to the opposition of the slave trade.

The story behind this unique beach fits the quirky history of Key West to a tee.

In 1860, 1,432 Africans were freed from slave traders and taken to Key West, where they were quarantined for a time. Residents visited and cared for the quarantined captives, and the lucky ones were returned to Africa.

About 300 died in Key West and were buried in unmarked graves along the island’s southern shore. As time passed, the burial site was forgotten.

Today, the cemetery is part of a 16.5-acre beach park along the ocean side of Key West. It hosts the only shore-accessible underwater marine park in the United States, and its location puts it close to Duval Street, the island’s popular tourist district.

The park offers swimming and snorkeling to volleyball and pickle ball. There’s a beachside café, a Civil War fort and a two acres of gardens with ocean views.

Besides being the home of the largest African Refugee Burial Ground in this hemisphere, the beach is also home of one of the largest AIDS Memorials in the country.

In 2001, research unveiled the first unmarked graves. By 2010, 115 more graves had been discovered. In many communities, the discovery that a public beach had been built on a cemetery would have produced a debacle. Not so in Key West.

The community instead pushed for historic recognition, which ultimately resulted in the beach being listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and community leaders invited African tribal dignitaries to consecrate the burial site, which is adorned with bronze plaques and African Adinkra symbols.

Read more: Higgs Beach: Memorial speaks to Key West’s cultural heart

Noteworthy Historic Sites

Lincolnville

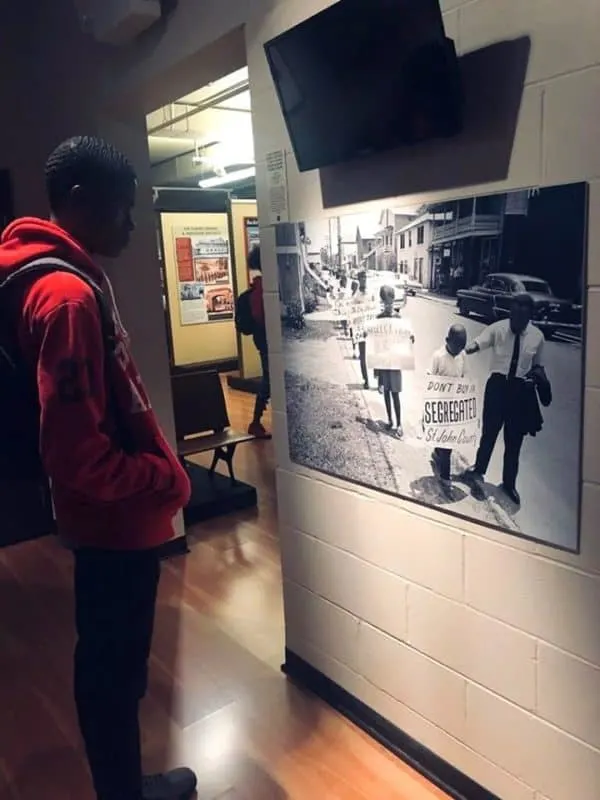

America’s oldest city, St. Augustine, offers a lot of Black history, from the who found freedom as Spanish soldiers at Fort Mose to the downtown memorial of the 1964 Southern Christian Leadership Conference campaign that marked the most prominent civil rights protest in Florida.

Lincolnville, the city’s historic Black community, is its centerpiece.

The community was established by free men and women in 1866, just after the Civil War, in an undeveloped area southwest of Saint Augustine. The area got its name from President Abraham Lincoln.

As the town grew, so did Lincolnville, particularly during the 1880s when Standard Oil magnate Henry Flagler began redeveloping parts of the city to attract wealthy vacationers.

Lincolnville produced the nation’s first Black professional baseball team, the Cuban Giants, composed of Black waiters who worked in nearby hotels.

During the height of the Civil Rights Movement, local activists appealed to Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in their efforts to integrate public facilities and schools. The ensuing march from Lincolnville to the old slave market in the city’s downtown historic district resulted in the arrests of hundreds.

Lincolnville began to change following the end of legal segregation. Over the years, many of the area’s middle-class professionals moved to newer, suburban areas. Still, the city recognized the area’s architecture and history. In 1991, the Lincolnville Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The area, like many one-time predominantly Black communities located near downtown areas, retains much of its historic beauty, along with several historic markers, marking Black Catholic Heritage, Zora Neale Hurston and the district itself. Self-walking tours are a relaxing complement to the city’s more famous historic district.

Read more: Lincolnville Historic District

Harry T. & Henriette V. Moore Cultural Complex

The marker near the front door of the complex tells the story of one of the nation’s first martyrs of the Civil Rights Movement.

The complex, just off the Mims interchange on Interstate 95, is a fitting memorial to an activist couple who died for their belief in a better America.

In 1934, the Moores founded the Brevard County chapter of the NAACP. Harry Moore would help organize the statewide NAACP organization and become its president. He worked to recruit new NAACP members, raise pay for Black teachers, investigate lynchings and file lawsuits against voter registration barriers.

In 1946, both the Harry and Henriette Moore were fired from their teaching jobs, a common tactic used to discourage Black activism. Without his day job, Harry became even more active and ultimately establishing the Progressive Voters League which succeeded in increasing the registration of Black voters to a point higher than in any other southern state.

In 1951, after the Moore family had returned to their home in Mims from a Christmas Day family dinner, a bomb exploded underneath their house.

Moore died on the way to a Black hospital about 30 miles away. His wife, Henrietta, died nine days later. The case remained unresolved until a state investigation that ended in 2006 named four Ku Klux Klan members who had long since died as the likely perpetrators.

A replica of their home now stands on the site of the original Moore home. The interior was modeled to look like the original home on the evening of the bombing.

The nearby museum offers artifacts, interactive exhibits, historic collections to detail the couple’s activities as civil rights activists.

Tours are available on request, and the complex contains an outdoor pavilion that can be rented to accommodate up to 150 guests, a large conference room and a gazebo for weddings, retreats and other events.

The overall mission of the complex is to serve as a civil rights resource and tourist center.

Read more: Harry & Henriette Moore Cultural Complex and Museum

Worthy Road Trips for Florida Black History

Fort Gadsden: “The Negro Fort“

Fort Gadsden is perhaps Florida’s least accessible historic site. The Battle of the Negro Fort was the only time in American history in which the United States military destroyed a community of escaped slaves in another country, then Spanish Florida.

What had been a fugitive slave community in Florida so scared slaveholders in the American South that the U.S. government sent soldiers led by General Andrew Jackson to destroy it.

The Negro Fort is now the Fort Gadsden National Historic Site.

The fort was a British garrison built after the War of 1812. The British offered freedom to slaves from nearby Georgia and other southern states who would live in and protect the fort strategically located on the Apalachicola River.

The British ceded the post to Spain, which kept the freedom offer intact. Besides a growing number of Black inhabitants, the British also left enough arms and ammunition to discourage American slaveowners from attacking.

In 1816, the U.S. government sent troops into Spanish Florida to destroy the fort. A red-hot cannonball struck the fort’s gunpowder magazine, killing 300 inhabitants in an explosion heard in Pensacola, 100 miles away.

In 1818, a new fort was built and named Fort Gadsden, after the lieutenant who oversaw its construction. Three years later, the United States took possession of the Florida territory.

The park now consists of the remains of two forts: the first built built by the British in 1814 and the second built and designed by Lieutenant James Gadsden. There’s not much actual fort left. A malaria outbreak forced Confederate troops to abandon the fort for good.

What does remain is a historical marker, a picnic area and a hiking trail with interpretative kiosks that explains the story of the two forts. The trail leads visitors to the Apalachicola River and the site of the original fortress and the “Renegade Cemetery,” where many of the fort’s Black inhabitants who died in the explosion are buried.

In a nearby clearing, there’s a marker and a burial vault that commemorates those who died defending their freedom and their respect for the British who gave them refuge.

The site sits on Prospect Bluff overlooking the Apalachicola River in the Apalachicola National Forest.

It’s a pretty remote place, perfect for hiking or camping and hunting in the nearby national forest. The park itself should interest anyone who likes the great outdoors and won’t mind seeing the words ‘No Service’ on their cellphones.

Unfortunately, the park is located in a such a remote area, it doesn’t attract enough visitors who would appreciate the site’s significance as a symbol of freedom and a testament to the resistance of American slavery.

Read more: Prospect Bluffs: Fort Gadsden

fort-gadsden

Rosewood

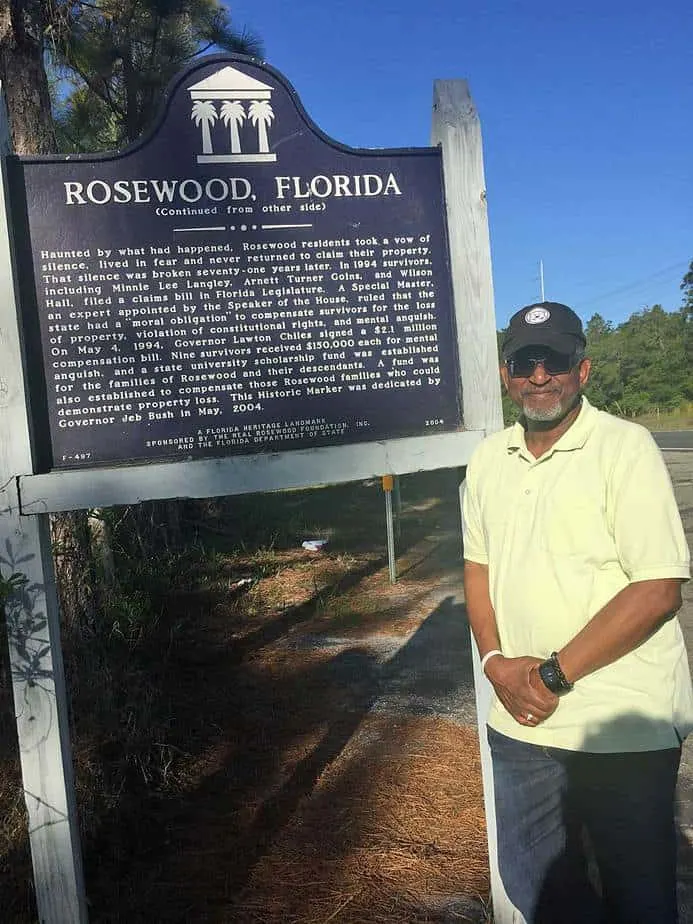

The state marker is the only sign of the area’s historical significance. Blink as you cruise past open fields along this stretch of State Road 24 approaching Cedar Key, and you just might miss it.

What now passes as idyllic, open road scenery was once the scene of a racial massacre.

Until January 1923, the village of Rosewood was a quiet, self-sufficient, racially segregated, community of Black residents in rural Levy County. The town got its name from the reddish color of the cedar wood that was once cut and processed there.

The community consisted of more than a dozen two-story wooden plank homes, three churches, a school, a Masonic Hall, two mills, two stores and a baseball team — the Rosewood Stars.

All that changed when word spread throughout the county that a white woman had been assaulted by a Black drifter.

What came next was swift and deadly.

A mob of several hundred whites combed the countryside, hunting Black people and torching the village, prompting residents to flee and hide in nearby swamps for days.

At least six Blacks and two others were killed, although eyewitness accounts suggest the death toll was much higher. Shamed and scared, the survivors, their descendants and the perpetrators stayed silent about the massacre for years.

The story of Rosewood resurfaced in the early 1980s as journalists became interested in the massacre. The renewed attention prompted a group of survivors and their descendants to sue the state for failing to protect Rosewood.

In 1993, the Florida Legislature commissioned a study, which led to the state ultimately compensating the survivors for damages from the riot. In 2004, the state designated the site of Rosewood as a Florida Heritage Landmark.

The historical marker is pretty much all that is left. Go another nine miles south on State Road 24 to the island community of Cedar Key, Florida’s second oldest town (after St. Augustine).

Read more: End of the world: Pack the RV for Cedar Key

More stories about Florida black history…

- Discover Florida’s Black history by following the signs

- State park honors civil rights leaders‘ “Saltwater Railroad“

- America’s first free Black settlement was in Florida

- Kingsley Plantation: A Florida story of slavery

- Once the ‘colored beach,’ state park honors civil rights leaders

- Legend of Black Caesar haunts the Florida Keys

- A low point in Florida History: The Rosewood massacre

Douglas C. Lyons is a contributing writer with a deep interest in the influence of African-Americans on Florida’s development and history. An explorer, a veteran journalist and editorial writer, Doug has lived in Florida for nearly 25 years.

Mike Hughes

Monday 7th of February 2022

I like history. I don't put colors on my history.

Kathy Rayson

Monday 1st of February 2021

Great story. Thank you.